Jim answers questions from fellow Drillers

(More questions with answers here, Work Overview here, Index of concepts here)

Topic Overview

Hi again folks, Jim Novo here.

HIgh end hardgoods. One of the most difficult retail categories to deal with from a customer retention perspective, both offline and online. Only vehicles are tougher. In some ways, the category can be easier online, but perhaps not for a single local store due to competition. So what’s the best way to attack the repeat purchase peoblem? Focus on where you have the highest likelihood of success – 2nd purchase Latency. Ready for the Drillin’?

Q: I loved your book, thanks. Armed with it, I feel like I can achieve much more than most small retailers in terms of CRM.

A: Thanks for the kind words!

Q: I have a question though. I sell relatively high-priced furniture and design items, and as this is our first year of business, our inventory is pretty small. As a result, my Frequency totals range from 1 to 4. That’s it, after a year of business. About 75% of our customers have bought once and it “ramps up” to 4 from there. I use “ramp” in the broadest sense of the word.

A: Yep. That’s the hardgoods business, especially on the web. Don’t beat yourself up, it’s early in your game with lines like these, and don’t blame it too much on inventory either. In the long run, it’s better to sell the *right* stuff than everything you can find, trust me.

Q: So when I compute RF quintiles, the totals don’t cleanly fit within quintiles. In other words, for RF scores of X1 X4, customers have purchased once. X5 customers have purchased 2, 3, 4, or 5 times. If I raise the hurdle and only look at customers who have purchased more than once, I still can’t fit them cleanly in five quintiles.

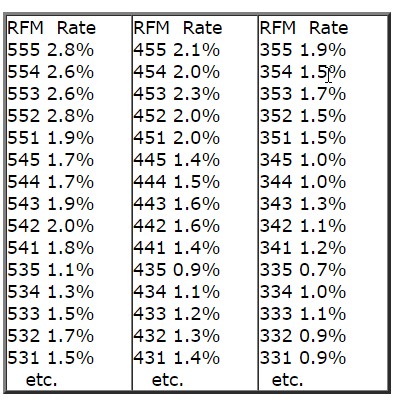

A: That’s one problem with RFM, it’s a bit robotic and works best with larger (usually meaning older) databases…

Q: I read your article on durable goods purchases and avoiding the one-time-buyer problem. I guess I’m looking for advice on how to make the “F number” significant until we’ve been in business long enough to get a broader range of frequency options.

Continue reading Second Purchase Marketing