“Yes, things are sweet,” thinks the owner of IMissAsia.com (not the real name of the site), ending a phone conversation with a supplier. Who would have thought! In just one short year, with the remains of the dot-com bust scattered all about, IMissAsia.com was running at sales of $25,000 a month. With an operating margin of 40%, “The Miss,” as the owner liked to call the site, was going to generate about $120,000 this year pre-tax – certainly enough to keep the spouse warm, fed, and reasonably happy.

Who knows what next year would bring? Could the business double in size? The owner figured The Miss could do about $2 million in annual sales with the current infrastructure set up – a web site / shopping cart that cost about $40 a month and assorted software / hardware purchased for a total of about $1,000. The owner put up the very simple web site and ships every box – the order management system is highly integrated with both the shopping cart and UPS WorldShip, so order processing and customer service are a breeze. All other costs of the operation were basically variable to sales. Sweet, indeed.

Of course, the owner / only employee has done a lot of things right in the first place.

IMissAsia.com is a site for people who used to live in Asia and now don’t, and are scattered all over the world. The core business idea takes natural advantage of what the web is very good at – aggregating niche vertical demand.

A person who used to live in Asia but now doesn’t is cut off from a lot of things they liked and now “miss” – food, clothing, beauty items, culture. IMissAsia.com aggregates all those things into one web site, and then offers it as a “one stop shop” to a very geographically dispersed group of people all over the world. IMissAsia.com is “patient zero” in all this, the intersection of diverse needs with a fragmented customer base – a perfect application for the web.

The site is set up smartly, using mostly free resources to attract and hold on to traffic – news feeds, free newsletters, and discussion boards. The store is tightly integrated into all the content, so there are many opportunities to get visitors to take a peek at the merchandise. The Miss gets pretty high natural search rankings for important search terms because it’s a plain HTML site without a lot of script and database-driven components, and has been written carefully with search engine optimization in mind.

In other words, the site is a little cash machine that requires almost no maintenance. Shipping packages, customer service related to those shipments, and the newsletter are about all the day-to-day work done on the business. However, storm clouds are on the horizon.

Response to the weekly newsletter is falling, and the owner is thinking of going bi-weekly or even monthly. In addition, to try and keep response up, the owner has been discounting more aggressively in the newsletter, and this practice is starting to depress margin. This situation is of deep concern to the owner, because the newsletter generates a big chunk of sales volume.

Niche markets are a double-edged sword. While they fit perfectly into the natural search-driven model of the web, by definition, niches are small. This kind of business has a tendency to ramp up very quickly, but then plateau as the entire niche is discovered and filled out. You can quickly capture 80% of the market, but then there is nowhere to go.

And as soon as you are successful, you will attract copycats, who chip away at your share, often undercutting your prices in start-up mode. The copycats have now started to appear. How will the owner grow the business when it already dominates the niche, and defend against the copycats? Not to mention address the worrisome situation with the newsletter.

IMissAsia.com offers an e-mail newsletter on every page of the site. The owner tries to create a broadly appealing piece, mixing some new content with links back to areas of the site experiencing high activity – specific discussion boards, products, news clips, etc.

The owner has always felt the visitor / customer should drive the direction of the site; if certain topic areas were getting the most traffic, then those must be the most interesting or attractive topics, and likely the ones with appeal to the most people. This “swim with the tide, not against it” approach had always worked well in the past as a driver for newsletter content.

Within this content, the owner carefully mixed contextual sales opportunities directly related to the content, along with one or two more aggressive product pitches. This formula had worked well and the newsletter drove a good chunk of sales.

But the owner of IMissAsia.com was getting worried about response to the newsletter, which has been falling. Perhaps swimming with the tide was not a good idea, and the content should explore “not popular” issues and products? Perhaps the product pitches were too frequent and aggressive? Perhaps this market was just slowing down because of the economy? Or worse, perhaps the owner had already “creamed” this market and the best days were over?

One thing the owner knew for sure – the percentage of total sales from new customers was falling. Now, this could be a good thing, the owner thought, because it means more sales are coming from repeat buyers. But it could be a bad thing, if what it means is the market is saturated and the best days are over. How to resolve this question? And how is the newsletter affecting this issue, if at all?

The owner thought a lot about new customers, repeat customers, and the newsletter. What is a “new” customer, anyway? Are they new only the day they make a first purchase? Are they still new if they haven’t made a purchase 30 days later? 60 days later? 6 months later? Do they have to make a second purchase to not be “new”? When do they stop being new?

For that matter, when is a customer not a customer any more? If they purchased twice or more and have not purchased again for 6 months, are they still a customer? What about no purchase in 2 years? 5 years? When do customers cease to be customers? What does the customer base of IMissAsia.com really look like?

The owner realized the only way to answer these questions was to actually look at the customer data, and to make decisions on what these ideas meant for this business. Customer types for IMissAsia.com probably would not be defined the same way as a customer types for Boeing, Wal-Mart, Oracle, or Ford. No, these customer definitions needed to be based on the facts of this particular business model.

The owner also realized something else – if there are no definitions, there can be no measurement. And without measurement, there is no way to understand the dynamics of what is happening to the business, for example, why the response rate to the newsletter is falling. All the owner knows is one thing, the “what” – response is falling. The owner wants to understand “why.” And there is no way to get to “why” without understanding the “who” first.

Response to the newsletter is falling because not as many customers are responding. Who is not responding to the newsletter? Is it new customers? Is it repeat customers? Is it “best customers”? The owner realizes there is no definition of best customers either. If these things were defined, the owner might be able to measure and understand what is happening. Then another realization – not just defined, but tracked over time. It does no good to define customers and count how many there is of each type; what the owner needs to know is how these counts are changing over time.

And since the specific topic at hand is the newsletter, what the owner needs to do is not only define the customers, but also to define them relative to the newsletter. What percent of new customers respond now, and over time? What percent of “old customers” respond, now, and over time? What percent of “best customers” respond, now, and over time? Knowing these numbers would almost certainly help the owner understand why response to the newsletter is falling overall. The owner resolves to address this situation immediately by digging into the data. Yes folks, the inevitable Drilling Down…

If different types of customers were defined, the owner might be able to understand what is happening. What the owner needs to do is not only define the customers, but also to define them relative to the newsletter. What percent of new customers respond? What percent of “old customers” respond? What percent of “best customers” respond?

When thinking about defining new customers, customers, best customers and so on, one concept keeps coming up, and that is “how long.” How long has it been since the customer last made a purchase? Surely this concept must have a direct bearing on defining customers; at some point a customer who has not purchased in a long time is no longer really a customer, the owner thinks.

Also, at some point a customer who made a first purchase is no longer a “new customer” – they’re just a customer. A “best customer” would also need some kind of definition involving last purchase date.

For example, customer #1 who purchased $500 in the past month must be more valuable than customer #2 who purchased $500 2 years ago and has not purchased since. It seems to the owner customer #1 is much more likely to buy again than customer #2; if this is true, customer #1 has a higher value to the business, because customer #1 has a higher likelihood to buy even more. This “future value” makes customer #1 more valuable than customer #2.

The owner’s brain was starting to hurt thinking about all these possibilities, and it seemed like time to quit thinking and “do something” about it. Since last purchase date seemed like the most critical element, the owner decided to classify the IMissAsia.com customers by last purchase date, and then take it from there. Perhaps the data would spark some ideas on how to think about and define customers.

The owner decided the easiest way to do this would be to put customers in monthly “buckets” of 30 days each – last purchase date 0 – 30 days ago, last purchase 31 – 60 days ago, last purchase 61 – 90 days ago, and so forth. By creating a standard classification like this, the owner could compare the number and percentage of customers in each bucket month to month, and see what was happening to the customer base. The owner was not quite sure what to do with this information, but knew one thing – if the percentage of customers purchasing Recently was low and the percentage not purchasing in a while was high, that could not be a good thing.

The owner completed the calculations and found the following percentages of customers in each “Last Purchase Date” bucket:

What Percentage of Customers Last Purchased How Many Days Ago?

| Days | Percentage |

| 0-30 | 3% |

| 31-60 | 6% |

| 61-90 | 10% |

| 91-120 | 14% |

| 121-150 | 16% |

| 151-180 | 20% |

| 181+ | 31% |

| Total | 100% |

The owner of IMissAsia.com was devastated.

Things looked bad, the owner thought, but what did this information really mean, and what could be done with it? It appeared as if the customer base was “sliding downhill” or aging; the largest group are customers who have not purchased for a very long time, almost like people would buy, then give up, and fall down to the bottom of the “purchased recently” barrel.

The owner used to think of all customers as pretty much equal, they were just “customers,” and all equally likely to buy at any time. But to see this, the customer base kind of looks like a pyramid in time, with very few people at the top and a huge number at the bottom. What did it mean?

Fellow Drillers, I encourage YOU to do a “30-60-90,” as I call it, on your own customer base. You will find it looks very similar in form to the one from IMissAsia.com. Pick any activity – purchases, visits, board postings, game plays – and rank all your customers, not just a group you choose, by how long it has been since they engaged in that activity.

You will find your very own activity “pyramid” in your customer database. Compared with IMissAsia.com, it may be “flatter” or it may be “taller,” but you will generally see a much smaller percentage of customers in the most Recent group than you will see in the least Recent group, very often by a factor of 10.

Of course, the real question is, what can you do with this information, how can you change this state of affairs, and how much money can you make doing it?

Pondering this question, the owner went about the usual business tasks for the day. Scanning the new newsletter subscriptions, the owner notes the different sources producing the majority of new subscribers, then moves on to process orders for the day. Folks, recall that response to the newsletter has been falling, and the owner was pleased to see the latest newsletter generated decent order activity.

As usual, some orders stood out from the rest; the owner recognized repeat buyers and people who had just placed an order Recently. “What makes them do that, I wonder?” thinks the owner. They buy something then they buy something else only a week later. Why don’t they buy both at the same time? They could save money on shipping, the owner thinks…

As the owner processed orders, thoughts returned to the 30-60-90 bucket analysis. I have all these orders, day after day, the owner thinks, yet most customers have not bought from me in quite some time. How is this possible? It doesn’t make any sense.

Then the owner has a brainstorm. What would the 30-60-90 Last Purchase Date information look like just on people who responded and purchased from the recent newsletter? I could match people who bought from the newsletter with their Last Purchase Date before I sent the newsletter, and then could find out how effective the newsletter is at getting my “lost customers” – those who have not purchased in months – to buy again.

In other words, what percentage of people in each 30 day bucket purchased through the last newsletter I sent out? Perhaps this would provide the insight needed to demonstrate what this Recency data means, and provide some insight into the kind of action that needs to be taken to keep people buying for a longer time. The owner sorted responders to the newsletter according to the Last Purchase Date before the newsletter was mailed out, with the following results:

| 30-Day Buckets (Days Ago) | All Customers | All Newsletter Responders |

| 0-30 | 3% | 31% |

| 31-60 | 6% | 18% |

| 61-90 | 10% | 18% |

| 91-120 | 14% | 14% |

| 121-150 | 16% | 10% |

| 151-180 | 20% | 6% |

| 181+ | 31% | 3% |

| Totals | 100% | 100% |

The owner was slack-jawed. How could this be? Is it possible that (top row) almost 1/3 of the responses came from 3% of customers? That (top two rows together) nearly 50% of the responses came from 9% of customers? The owner’s head was swimming! What was the implication here? Is it possible – and just this simple – that the response rate of a customer to the newsletter could be predicted based on how many days ago they last made a purchase? The implications were stunning. One simple calculation. Incredible ability to predict purchase behavior.

But what to do with this information?

As the owner of IMissAsia went about the favorite task of the day – reviewing and packing orders – thoughts were on this topic of “doing something” with this Recency info. The owner then noticed orders coming in from the “CRM program” started last month for best customers. Finally, some good news.

It was a very simple idea really – the owner took the time to identify best customers who had not shopped in 180 days and sent them a special discount. This idea came from a friend in town who had a hair salon. It was a really big discount thought, and the owner disliked seeing all that margin go out the window, but was happy to have the orders. If the only way to get them to respond was to be aggressive, so be it. After all, it was very targeted, and generated large orders.

Then it all hit the owner like a ton of bricks.

The less Recent a customer is, the less likely they are to respond. So you should be able to “rank” customers by likelihood to respond. But what if customers go through “stages” of being likely to respond, a predictable “cycle”? As the customer drops through 30 day, 60 day, and 90 day Recency, they become less and less likely to respond. With best customers, when they get to 180 days, it takes a huge discount to get them back, and not many even come back. What if I got involved in this cycle earlier? Why wait for them to get to 180 days before acting?

Right now, the owner thinks, I send the same 10% discount to everybody who gets the newsletter and the response varies by Recency – the more Recent the last purchase, the higher the response rate. So what if I altered the discount by Recency, giving a bigger discount to folks who were less likely to respond – the ones who are less Recent. In other words, vary the discount by the stage of the “cycle” the customer is currently in.

I could probably cut discount costs while increasing response rate, because I would not be giving away as much margin to those most likely to respond, and would be making more aggressive offers to those least likely to respond. Lower discount costs, higher response rates across the entire mailing.

But what is the right discount to offer for each Recency bucket? The more aggressive the discount offer, the higher the response, but higher response means more margin going out the window. Surely there is a “tradeoff” of low discount cost with high response for each Recency bucket, and it is probably different for each bucket – since “normal” response is so different in each Recency bucket. So all I have to do is test each bucket across a range of discounts to find out what discount is most profitable for each of the buckets!

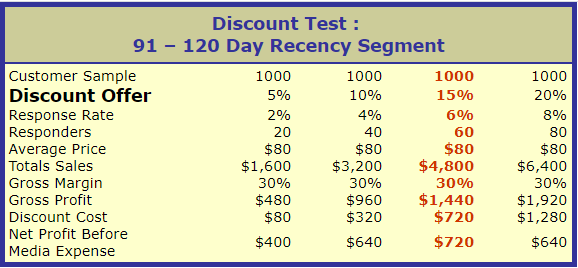

Looking at the buckets, the owner chooses the 91 – 120 bucket to test first because that is where customer response seems to really start trailing off; customers in this part of the “cycle” appear to be the most at risk to never respond again. So the owner divides customers in the 91-120 bucket into 4 equally-sized groups, and each group is sent a different discount:

The most profitable offer for the 91-120 day Recency bucket, the one that generates the highest response while giving up the least margin dollars, is 15% off – not the 10% off these people were used to seeing. And what is more, in subsequent repeats of this test, 15% off is always the most profitable offer to use with the 91-120 Recency bucket – the outcome of the promotion is consistent.

Well fellow Drillers, you can imagine how excited the owner of IMissAsia was to lower discount costs while increasing response rate. And if this approach works for the 91-120 day Recency bucket, it probably works for all the other buckets as well, don’t you think?

(Jim’s hint – it does).

But all the owner of IMissAsia.com has right now is a more profitable newsletter promotion. The biggest discovery – the one with the most potential to increase profits for IMissAsia.com – still lies right around the bend.

Click here to Continue with Part 2

or

Get the book at Booklocker.com

Find Out Specifically What is in the Book

Learn Customer Marketing Concepts and Metrics (site article list)

Download the first 9 chapters of the Drilling Down book: PDF