Let’s say you have decided to build a relationship with the CFO or a peer in Finance. How do you get started? Here are two report concepts and charts that will give you much more to talk about than you can squeeze into one lunch. By taking Finance’s own numbers (Periodic Accounting) and recasting them into the numbers that matter for Marketing (Customer Accounting) you create a very solid bridge and basis for building out a plan. Note to yourself: And the plan is? Make sure you think about that first…how can you help Finance / the Company achieve their Cash Flow and other Financial goals?

Report 1: Sales by Customer Volume

Core Concept: The idea here is to decompose a CFO’s financial quarter (or any financial period) into the good, better, best customer volume components that make up the financial period. It’s a “contribution by customer value segment” idea. Benefit: Graphically demonstrates to the CFO the “risk” component of customer value in the customer portfolio and supports the idea Marketing could mitigate financial risk by “not treating all customers in the same way”.

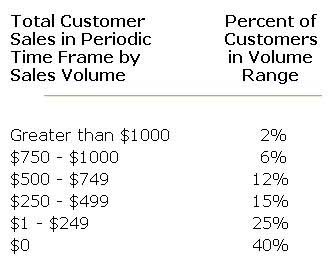

Take any periodic statement time frame – a month, a quarter, a year. Gather all the customer revenue transactions for this period, and recast them into the total sales by customer for the period. Decide on some total sales ranges appropriate to your business, and produce a chart on the percentage of customers with sales in each range, including non-buying customers, for the chosen periodic accounting time frame. For example:

Run this report each period, and compare with prior periods. In general, you want to see the percentage of customers contributing high sales per period to grow over time, and the percentage of lower revenue customers to shrink. This means you are increasing the value of customers overall. If the numbers are moving the other way, this is the type of customer value problem you would expect CRM or a smart retention program to correct, and if you are successful, you should see the shift in customer value through this report.

Report 2: Sales by Customer Longevity

Core Concept: This report is a “Flashcard”, if you will, that demonstrates the Customer LifeCycle. If you have trouble communicating complex LifeCycle / LifeTime Value concepts to Financial people, this Flashcard takes their own numbers and decomposes them into a vivid picture of why the LifeCycle matters. Benefit: Opens the door for your budgets to be determined by different metrics than are currently used; what good is a “quarterly budget” when the underlying customer issue can be much more dynamic? Wouldn’t the CFO like you to “do what it takes” in the Current Period to preserve profits in Future Periods?

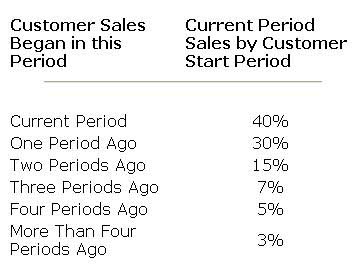

Take any periodic statement time frame – a month, a quarter, a year. Gather all the customer revenue transactions for this period, and recast them relative to the start date of the customer. In other words, when looking at the revenue generated for the period, how much of it was generated by customers who were also newly started customers in the same time period? How much was generated by customers who became new customers in the prior period? How about two, three, and four periods ago? More than 4 periods ago? Depending on the length of the period you use, you may end up with a chart looking something like this:

You can run this analysis at the end of each period and track the movement of customer value in your customer base. Generally, you want to see increasing contribution to revenue from customers in older periods, meaning you are retaining customers for longer periods of time and growing their value.

If this kind of idea interests you, the full background on explaining the LifeCycle / LTV to Finance is here.