A B2B software company has an appealing pitch to business – their software makes a company more efficient and saves more money for the company than the software costs. The software is modular, with a base application and additional add-ons that are specific to certain business challenges. The selling strategy is to underprice the base application to get market penetration and them make a higher margin on the add-ons. The add-ons drive the profitability of the business, as does the installation and customization of these add-ons.

The company has been quite successful with this selling strategy. But at a point, the CFO notices sales of the base application have risen but revenue from add-ons has not risen in the same proportion. In other words, the company is further penetrating the market but getting less revenue from each customer. The CFO thinks:

I can’t understand this. Sales of the base application are rising according to plan but overall company revenue is not growing at the same rate. The only thing I can think of that would create this particular situation is fewer basic application customers are buying add-ons. How can I figure out why this is situation is happening?

The CFO calls the heads of business development and marketing to ask about the situation. They both report they are aware of slowing add-on unit sales per customer, but cannot attribute it this to anything specific. The company is simply penetrating the overall market more deeply they say, and as we penetrate further and further, add-on sales seem to have slowed.

The CFO is not particularly satisfied with this answer, and thinks:

If it shows up in my financial statements, it has to be measurable. I’m just seeing this from too high a view. All the sales of the different base applications and add-ons roll up to total sales, so the data I need to better understand this must be somewhere.

The CFO picks up the phone to call the CIO, and then hesitates. The IT people are going to want to know specifically what I am looking for, the CFO thinks. Do I really know?

Jim says:

What is needed here, fellow Drillers, is quantification, some framework for analyzing the situation. What is the real question to be answered here? The CFO knows IT has limited resources to apply to this kind of ad hoc work – if the request just generates information that leads to another question, precious time and resources are wasted.

The CFO could ask for monthly product sales percentage by type over the past year. In a lot of ways, this information would simply confirm what the CFO already knows – sales of add-ons have gone soft. But does it answer the core question of *why* they have gone soft? That is the real question at hand. It does not. Customers do in fact have different LifeCycles to them (see Customer LifeCycles ) so any monthly sales data will contain customers in various stages of being likely to buy an add-on. Raw monthly financial data – the kind the CFO is used to working with – is not going to answer the “real” question. The CFO thinks:

Customers buy the base package and once they get it integrated and tuned up they start to buy the add-ons. During any one-month period, we have customers who just bought the base package, customers who are in different stages of integration, and customers who are buying add-ons. What I really need to know then is this: what is the average number of weeks between the purchase of add-ons, this year versus last year? If this number of weeks is rising, that is where the softness in add-on sales is coming from – customers are simply taking longer to make the purchase decision. If this number of weeks is constant or falling, something else must be going on.

With a more concise definition of the answer required in hand, the CFO picks up the phone and calls the CIO.

Does the data exist to do the required analysis? Are there staffers who can run the query? Will the CIO tell the CFO that since the CFO cut staff, there is nobody left to run the query, and the CFO needs to hire people to run ad hoc queries?

The CFO gets the custom report on the average number of weeks between customer purchases of add-ons. It looks like this:

Average Weeks between Add-On Purchases

Last year 8.6 weeks

This year 8.9 weeks

So it is taking longer for them to purchase, the CFO thinks, and darn it, now I have another question. The IT people are going to have me for breakfast for not thinking this all the way through the first time! I got the information I asked for, but this information is not actionable, I can’t do anything with it. There is not enough detail to act.

Fellow Drillers, when you are plumbing the depths of your data, try to think of what you will do with the information you are asking for. Imagine getting back your results, and taking an action based on those results. If you can’t imagine the action you would take knowing the information, you are not asking the right question yet. The CFO thinks:

Our add-on modules have different prices and different levels of difficulty involved in their integration. And they are usually installed in a particular sequence. So what I really should have asked for is the average number of weeks between the purchase of add-ons by add-on – the time between base purchase and the first add-on, the time between the first add-on and the second, and so forth.

Maybe there are problems with installing one of the add-ons due to changes in the next generation of operating systems, for example, and this is slowing the installation of a particular add-on down. If I can get the average number of weeks between add-on purchases by add-on, I can act on this, because I will know which add-on is causing the slowdown in sales.

The CFO reluctantly picks up the phone to call the CIO. At least this time, the CFO thinks, I have thought the question out all the way through, and I know what action I can take with the information once I get it. Shortly after a heated exchange involving resource allocation, budgets, and a hiring freeze in IT with the CIO, the CFO gets this report:

Average Weeks between Add-On Purchases by Add-On

| Last Year | This year | |

| Base app to 1st add-on | 12.3 weeks | 12.1 weeks |

| 1st add-on to 2nd add-on | 10.5 weeks | 10.2 weeks |

| 2nd add-on to 3rd add-on | 8.7 weeks | 8.9 weeks |

| 3rd add-on to 4th add-on | 6.1 weeks | 6.7 weeks |

| 4th add-on to 5th add-on | 5.2 weeks | 6.5 weeks |

| Avg. time between add-ons | 8.6 weeks | 8.9 weeks |

Fellow Drillers, it would be nice if the pattern was a bit more clear, yes? It appears customers are ordering their first and second add-ons more rapidly than last year, but as they get to the third, fourth, and fifth add-ons, they are ordering more slowly than last year. What could this possibly mean? The CFO:

Well, I answered my question, but I’ve got another. The reason why add-on sales appear soft is a longer purchase cycle for the average add-on, and the reason this is happening is the later add-ons are taking much longer to be purchased than they were last year, even though the first add-ons seem to be cycling much more quickly. What does that mean? I promised the CIO I would be able to act on this information, and I simply can not.

Will the CFO beg the CIO for more reports? Will the CIO extract a hiring deal out of the CFO in return for supplying the reports? Just who the heck is going to do all this analysis work anyway? And the deadly question – what is the ROI on all of this noodling?

Fearing another phone call right away to the CIO, the CFO thinks:

What I have here is change. There has been a significant change in the way this business works for some reason. Change doesn’t happen in a vacuum though, something must have caused these changes to happen, a significant event now being reflected by these average weeks between add-on purchase numbers. What could it be?

The CFO remembers the heads of biz dev and marketing saying the company was “penetrating the overall market more deeply, and as we penetrate further and further, add-on sales seem to have slowed.” Was this the change the CFO was looking for? What did it really mean, in terms of how the business may have changed?

Getting the heads of biz dev and marketing on the phone again, the CFO asks if this market penetration situation had created any changes in the way the company does business. The CFO hears for the first time about a new trade campaign and a new sales person hired to address a particular market segment. This is must be the change the CFO was looking for!

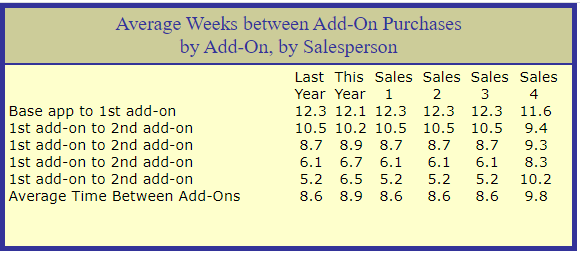

Gingerly, most humbly, the CFO calls the CIO once again. This time, the CFO wants to see average number of weeks between add-on installs by add-on by salesperson. After a promise to review the hiring freeze is extracted by the CIO, this report is delivered:

And there it is. Clients of Salesperson # 1, # 2, and # 3 are purchasing add-ons at the same rate they did last year. The clients of the new salesperson # 4 are purchasing in a dramatically different pattern, with much shorter cycles purchase cycles in the beginning and much longer cycle purchases later on. Literally, the LifeCycle of the customers in this market segment are different from the LifeCycles of the average customer from previous years, and dramatically so.

It takes these customers on average 14% longer to purchase any add-on – 9.8 weeks versus 8.6, or 1.2 weeks. Over the entire purchase LifeCycle of the add-ons, this increases the purchase cycle by 4.8 weeks (1.2 x 4). If this new segment is doing a lot of dollar volume compared with the old segments, this could significantly affect sales and make add-on purchases look soft – even though they are in fact getting purchased!

At his moment, the head of biz dev appears in the door with another person who turns out to be new Salesperson 4. The CFO looks up and the head of biz dev, somewhat sheepishly, introduces the new salesperson.

“Glad to meet you,” the CFO says. “By the way, can you tell me something? Do the customers in your new segment purchase and install our add-ons in the order we suggest in our operations manuals?”

“No, they don’t” said Salesperson # 4. They install them in a different order, because they are having some difficulty installing a couple of the add-ons, and usually delay those to the end of the purchase cycle when they have more experience with the applications. Is there something we can do about that?”

The CFO just smiles, and thinks:

Looks like I just found the money to pay for unfreezing some hiring in IT.

“I think so,” the CFO tells new Salesperson #4, calculating the improvement in cash flow if these add-ons were installed faster on the fly. “I really do think so.”

That’s it for the B2B Software Example using Latency. The Latency metric is a rock-solid behavioral marketing tool – a bit blunt, but always a good place to start, sort of like the rough sandpaper or the ripsaw. I often find when beginning a project, hunting around for Latency variances does not provide the answer, but serves up plenty of clues to get you going in the right direction.

The B2B Software Example points out the need for reconciling the differences between financial and customer accounting in a customer-centric business. For more on how this concept applies to CRM implementation, you might want to read this case study on the link between salesperson behavior and customer retention in cable systems.

Get the book at Booklocker.com

Find Out Specifically What is in the Book

Learn Customer Marketing Concepts and Metrics (site article list)

Download the first 9 chapters of the Drilling Down book: PDF